Mike Breen: The Architect of Coercive Control

When Discipleship Becomes Coercion: A Deep-Dive into the Safeguarding Risks of Breenism.

Transparency Notice

This post was written pseudonymously. Learn more about our editorial ethics .

Support and Reporting

This article discusses coercive and abusive behaviours in faith spaces, which some readers may find distressing. Take breaks if needed and seek support if you recognise these patterns.

- Action on Spiritual Abuse (UK)

Survivor-focused support offering structured, medium-term guidance and practical next steps.

- Thirtyone:eight (UK)

Independent safeguarding advice for concerns in church or Christian settings.

Helpline information 0303 003 1111

In an Emergency: If you or someone you know is in immediate danger, or if you believe a criminal offence has been committed, you should contact the police.

Outside the UK, contact a local survivor support service or national abuse helpline in your country.

Introduction

We learnt too much at school

Now we can’t help but see

That the future that you’ve got mapped out

Is nothing much to shout about

There’s an old saying, often attributed to Mark Twain, that cuts straight to the heart of why smart people make catastrophically bad decisions: ‘It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble - it’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so’.

When it comes to Mike Breen, most people in Christian leadership circles know plenty. They are familiar with LifeShapes, particularly the ubiquitous triangle that maps our relationships with God (UP), each other (IN), and the world (OUT). They know he moved to America and built 3DM into an international ‘movement’, selling books, courses and consultancy to churches hungry for discipleship frameworks that claim to work. They may even know he wrote the playbook on Christian communication strategy, Speak Out1, and discipleship, Building a Discipling Culture2.

And, of course, they are aware of the scandal. In 2024, an independent investigation found that Breen had engaged in what his former organisation confirmed was ‘adult clergy sexual abuse’ with a vulnerable member of the church that he was leading3. They know this led to his resignation. They might see that he is facing a safeguarding investigation4 by the ‘Order of Mission’ (TOM), an order set up to share Breen’s vision on LifeShapes and discipleship. And they know, because everyone keeps saying so, that personal failings don’t invalidate effective techniques - that we must separate his methods from the man himself, that the tools are bigger than Breen anyway. They know that the tools are valuable. The techniques work. Good discipleship is still good discipleship, right?

Adult Clergy Sexual Abuse (ACSA)

A list of resources for survivors of abuse from Baylor University

Yet this widespread confidence in separating Breen’s methods from his conduct rests on a fundamental misunderstanding of what his framework teaches. A reader may ask: Doesn’t the methodology found in Breenism represent neutral tools for spiritual growth? The argument in this article is that Breenism should be understood differently: as a system that can easily lend itself to psychological conditioning and control. The spirit of this critique is one of conviction, not condemnation, aimed at equipping leaders to see the profound risks in this methodology. Within his framework, “accountability” becomes a mechanism for enforcing submission, while “discipleship” takes on characteristics that the Church of England itself would classify as spiritual abuse5. The personal failings and the published methods are not separate phenomena - they are manifestations of the same underlying approach to power and influence.

Extracting the ‘good’ techniques from a ‘bad’ situation represents a profound miscalculation, one that Breen appears to have made thirty years ago when he first developed these techniques as Rector of St Thomas’ Church, Sheffield, and one that continues to be made by leaders implementing his methods today. With Breen’s return to ministry, there is an urgent need to examine the gap between what people know for sure about Breenism and what just ain’t so .

The Appeal

To answer that question, we must examine what motivates leaders to continue embracing these methods even when warning signs emerge.

Why Leaders Embrace Breenism

This article will refer to his specific framework as Breenism . The distinction is critical. It separates his prescribed methodology from the universal Christian concept of discipleship. When advocates present a system as ‘Building a Discipling Culture’, they can deflect any critique of its methods as an attack on discipleship itself. Naming the ideology allows us to analyse the specific product being sold, not the banner under which it is sold. By defining Breen’s packaged ideas as ‘Breenism’, we can clarify an important question. What compels leaders to adopt Breenism and begin leading huddles in their churches?

This appeal is powerful because it speaks directly to a deep anxiety felt across the Church. Faced with an existential crisis of declining attendance, ageing congregations, and evaporated cultural authority, leaders feel a profound need for solutions that go far beyond simple new ideas. The Church of England’s official strategy for this decade reflects this urgency, identifying the creation of ‘A Church of Missionary Disciples’ 6 as a core priority.

This directive has cascaded down through every level of the institution, placing immense pressure on parish leaders. Their task is now to actively form people into followers of Jesus day by day, not just manage Sunday services. Yet this official mandate rarely comes with a manual. Vicars and lay leaders, already stretched thin, are left asking, “How?” In a landscape with few models and genuine uncertainty, a systematic program promising clear frameworks and tools becomes enticing.

Breenism offers exactly that systematic program, and Breen packages it in the language of empowerment, authenticity, and relational depth. His analytical gifts are genuinely impressive; Breen can observe and deconstruct complex relational dynamics and can communicate them clearly in ways that feel revelatory.

He can accurately describe the mechanics of influence, persuasion, and psychological bonding but appears to lack the ability, the will, or the moral framework to recognise when his applications of these insights become manipulative. His ability to deconstruct such patterns and neatly package them creates a risk of moral inversion. Understanding patterns of influence can inform healthy pastoral care; deliberately engineering emotional dependency to discourage dissent or systematically leveraging vulnerability to consolidate personal authority constitutes a severe abuse of clerical power.

Dear reader, this is an important distinction that deserves mild repetition. It’s the difference between a leader who learns how wolves operate to protect the flock and one who uses that knowledge to become the wolf .

The problem is that many capable leaders facing genuine relational challenges hear Breen’s insights and think, ‘Finally, a practical manual on discipleship.’ His ability to deconstruct is impressive, and his frameworks appear sophisticated, claiming to be biblically grounded. But the very system that promises to make them better shepherds contains embedded mechanisms that risk teaching them to think like wolves. There is no intention to question the discernment of church leaders in the article. I am commenting on how expertly the framework disguises its true nature.

The urgency of the situation became clear in 2024.

The 2024 Safeguarding Crisis

The 2024 resignation shifted the ground under Breenism’s feet. Breen’s system had always raised red flags, but they were easily brushed aside. But when reports of an independent investigation confirmed that Breen had engaged in Adult Clergy Sexual Abuse , alongside patterns of bullying and intimidation , the concerns could no longer be dismissed as theoretical. The pattern had consequences.

Later that year, Breen returned to the UK and resumed ministry, doing so without visible oversight from established safeguarding authorities. This return to ministry raises ongoing concerns for risk management. In line with a survivor-first approach, I have refrained from speculating on their perspective. They have chosen not to make public comment, and that decision must be fully respected. From a safeguarding standpoint, however, the lack of publicly available detail about how the vulnerability was exploited limits the ability of others to assess specific patterns of risk. In such cases, the burden shifts to institutional actors and bystanders to adopt a posture of caution - treating Breen as a generalised and unpredictable safeguarding risk within any sphere of influence he occupies.

I offered Breen a formal right of reply ahead of publication. He responded via email, reiterating his belief in the integrity of the restoration process and disputing the investigation’s findings on bullying - arguing that these accusations came only from church leaders he had previously challenged, not from the church member at the centre of the sexual misconduct allegations. He declined to engage with the article’s broader questions, directed inquiries to the chair of his restoration team and stated that I should not contact him again.

Yet this immediate safeguarding concern, serious as it is, may not represent the full extent of the problem. What if the wider risk lies not only in what Breen did but in what he taught others to do — at scale?

The Methodology

Despite these concerns, there is no national or diocesan-level safeguarding pathway for addressing historic concerns about either Breen’s conduct or Breenism as a system. Apex Church (now Refuge Hill Church), which commissioned the independent investigation into Mr Breen, did not respond to questions regarding his public statements or whether the church had reviewed his discipleship models for this article. At Network Church Sheffield (NCS), Breen’s former church, where subsequent leadership teams firmly embedded Breenism, the Senior Leader also serves as the Safeguarding Officer, contrary to both the spirit and the letter of Church of England guidance. When contacted, the current leader of NCS described this as an ‘interim’ arrangement. This arrangement has been in place for at least two years.

This concern extends beyond immediate safeguarding to the broader institutional influence of Breen’s ideas. Research by Anglican scholar Jack Shepherd traces the ‘resource church’ concept - now central to Church of England strategy - directly to Breen’s 1997 writings about St Thomas’ Church functioning ‘as a resource to its city and region’7. When Ric Thorpe, now Archbishop-elect of Melbourne, described the foundational 2008 European Church Planting Network meeting in his influential book on resource churches, he was recounting a vision-casting session with the European Church Planting Network, with which Breen was closely associated.

When contacted for this article, Bishop Thorpe offered clarification on this point. He stated that his professional relationship with Breen was limited to Breen serving as ‘an invited guest who led some reflections each day’ at the 2008 event and that he had seen him only occasionally at conferences since then. Thorpe confirmed that the current TOM learning process ‘is primarily aimed at people’s experience, as members of TOM or those working with TOM’ and ‘is not a fundamental review of Breen’s published methodologies themselves’.

The Diocese of Coventry, coordinating the TOM Learning Process, confirmed no timeline for completion and did not respond to questions about public reporting. The Order of Mission’s Secretary confirmed an ongoing process with no specific timeline, encouraging those with concerns to participate in the learning process4. Furthermore, when I contacted the Church of England Diocesan Safeguarding Teams for Sheffield and Leeds regarding the specific risks of Mr Breen’s current informal ministry activities, no substantive response or statement was provided by either diocese at the time of publication.

To understand this wider risk, we must set aside the high-level vision and claimed benefits of Breen’s teaching to examine the specific methodology he prescribes. The danger lies in the actual, detailed content of what he advises leaders to do. The most transparent window into these mechanics is his foundational text, Building a Discipling Culture, where Breen lays out the psychological architecture of his system, using the image of a horse-trainer ‘breaking’ a horse as his core metaphor for discipleship .

The Horse-Trainer’s Manual

Raised on a diet of broken biscuits, oh

From this foundation, a pattern of contradictions emerges, all designed to function within a closed and exclusive environment: empowerment through submission, ‘gentle’ methods with controlling aims, unaccountable accountability systems, and a deliberate cycle of destabilisation and rescue designed to foster a profound dependency - not on God or their wider community, but personally and inappropriately upon the leader. The psychological power of this conditioning becomes even more stark when we examine how Breen explicitly models and justifies this process through what he describes as ‘The Jesus Model’.

To illustrate and justify a cycle of destabilisation and rescue, Breen builds his entire philosophy on an extended metaphor drawn from the work of horse-whisperer Monty Roberts. He presents this as a compassionate alternative to the overtly abusive methods of “breaking” a horse, such as Monty Robert’s father’s technique of frightening a horse “over and over” until he was “eventually able to break the spirit of the horse and control it in any way he wanted” or the other common practice of “beating the horse until its will was broken and the horse would submit to its master”.

Breen positions Roberts’s method as more “effective and more compassionate”, a distinction that focuses entirely on the means of control. He rightly condemns the overt violence of the old trainers, but this raises a more fundamental question that his analysis completely overlooks: Is the desired end, a “broken spirit” and a will that must “submit” to a leader, a legitimate goal of discipleship?

By presenting the problem as one of technique alone, Breen sidesteps the troubling implications of the intended outcome. His model is therefore offered not as an alternative to breaking a spirit, but as a more psychologically sophisticated method of achieving it. An examination of the mechanics reveals a process built on a repeating cycle of intimidation and reward, designed to arrive at the same destination: complete submission.

It begins with an act of dominance. The trainer, imitating a lead mare, turns toward the horse, flattens their ears, and looks directly into its eyes, using what Breen calls “the language and position of challenge”. The required response from the horse is total capitulation; it must adopt the posture of a juvenile by “pawing the ground and bowing in submission”.

Only after a disciple demonstrates this submission does the trainer offer a reward: the “offer of invitation”, where they turn their flank towards the horse. Breen frames this as a “powerful position of vulnerability and openness”, but within the cycle, it is a calculated release of pressure, a moment of intermittent kindness that provides relief from the preceding intimidation.

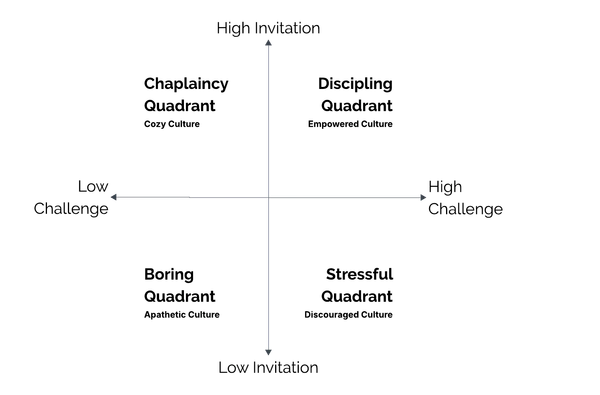

Many leaders interpret “invitation and challenge” as a broad choice about their church’s culture—whether to be more welcoming or more demanding. Breen’s four-quadrant matrix seems to support this view of establishing a static cultural posture. But his prescriptive examples tell a different story. His actual methodology doesn’t describe a fixed, strategic stance. It represents a frequent, repeating interpersonal cycle. In his foundational horse-training analogy, the process is explicitly “repeated until the two would eventually touch”. The clear implication is that disciples are to be kept in constant, dynamic tension between the leader’s approval and correction. This dynamic tension is a process of psychological conditioning designed to oscillate, not a static culture to be discerned and maintained.

Further evidence of this can be found in the last podcast on which Breen appeared before the investigation prompted his resignation. On July 23rd, 2023, he appeared on a discipleship podcast8, where he shared his thoughts on the constantly moving nature of invitation and challenge.

Invitation and Challenge - Jesus begins his ministry with an invitation, ‘Come follow me’. He completes his ministry with a challenge: ‘go into all of the world.’ It’s quite clear within those bookends of invitation and challenge, come and go; there’s a constant calibration of invitation and challenge.

This psychologically exhausting cycle of pressure and release should sound eerily familiar to anyone acquainted with clinical psychology. The dynamic, where a single figure systematically causes distress and then also provides relief from it, mirrors the precise conditions required to create what is known as ‘trauma bonding’ (more on this later).

He makes the explicit connection that this is his model for Christian discipleship, claiming that “Jesus was the ultimate horse-whisperer” who created a culture with an “appropriate mix of invitation and challenge”. He argues that all effective leadership is fundamentally based on this process. This single image is the key that unlocks the system’s appeal and masks its danger. It allows him to package a psychologically exhausting cycle of pressure and release as a compassionate and effective spiritual tool. What Breen champions as gentle “horse-whispering” closely mirrors methods known to induce trauma bonding - a more subtle methodology for achieving the same result as the abusive horse-trainer he critiques: a broken will and complete submission to a master .

This dynamic has played out in real churches with documented consequences. Matt Drapper’s experience during Form, a discipleship training year at St. Thomas’ Church Sheffield, provides a clear example. In his published memoir Bringing Me Back to Me9, he documents experiencing precisely this invitation/challenge cycle under church leadership that was operating directly under Breen’s methodology (the church had described themselves as being under Breen’s Spiritual Authority the previous year)10.

Drapper’s real-time journal entries reveal how Breen’s invitation/challenge cycle operates when the “challenge” becomes abusive. In a sermon on forgiveness delivered from the front of the church, the church senior leader at the time explicitly addressed LGBT supporters in terms so inflammatory that Drapper’s immediate response was to express his dismay, followed by “angry tweets” and emails demanding meetings with leadership.

The “invitation” phase followed immediately. After this public confrontation, Drapper describes receiving alternating punishment and reward: “For every angry tweet I typed up, someone would be kind to me out of the blue and make me feel the connection that I sought”. His journal entries track the psychological whiplash day by day. February 4th: After sending angry messages to leadership, he receives a text from Allan saying, “Know we love you very much”, which Drapper immediately recognises as potentially manipulative, writing “(And manipulative?)” in his journal. February 6th: another leader shows him “caring and unconditional love.” February 9th: “I feel sick and empty and done.” February 10th: the pressure culminates in self-doubt, as he writes, “I’m beginning to feel like I almost do need to go through the repenting stage (AGAIN).”

Drapper explicitly identifies this pattern using clinical terminology: “This was the kind of coercive control that held me in stasis at the Sheffield church during those months”. His account demonstrates precisely how Breen’s undefined concept of “challenge” can escalate to public targeting of vulnerable individuals, followed immediately by calculated displays of affection designed to create psychological dependency.

A defender of Breen’s model will rightly point to his use of positive and graceful language. He defines “invitation”, for example, as a relationship filled with “vibrancy, safety, love, and encouragement” and states that a “gifted discipler” applies challenge in “graceful ways”. This language gives the entire framework a veneer of safety and legitimacy. The problem, however, is that these positive aspirations are not attached to concrete, bounded actions. The term “challenge” is left dangerously undefined , creating a significant gap where any behaviour can be justified as a necessary spiritual exercise. This vagueness is not a minor oversight. It is a critical flaw that becomes evident when we examine how the concept of “challenge” functions in practice.

The Order of Mission, an organisation Breen founded, is currently leading a safeguarding ‘learning process’ into his time leading the organisation. An investigation of this kind is the predictable outcome of a system that prescribes intense, repeated “challenge” without providing any specific guidance, safeguards, or accountability to prevent it from becoming abuse. The positive language serves to mask a methodology that, in practice, often protects the challenger at the expense of the challenged.

Some will argue that the horse-breaking metaphor is merely a folksy illustration and that the actual model is Jesus’s interaction with Peter. I want to be clear here. I’m not criticising the concept of leaders correcting congregants. Correcting a follower in a respectful, considerate way is healthy. There must be clear reasoning, appropriate context, and genuine care for their well-being. What I struggle to find justification for is extracting a universal principle based on Jesus’ rebuke of Peter. Jesus’ correction came after Peter had fundamentally misunderstood Jesus’s purpose, putting the gospel itself at risk. To abstract this singular, foundational event into a repeatable technique for leaders to use on followers is a profound misapplication. Breen’s model transforms a unique moment of doctrinal, world-altering course correction into a routine tool for maintaining interpersonal tension.

Peter is only one example within a much broader design. Breen’s framework moves beyond metaphor, codifying his authority model into repeatable geometric forms. At the centre is what he calls the Leadership Square.

There is a meta-structure to much of what Breen discusses. The ‘square’ is the most foundational one within Breenism. It appears time and time again in different guises. The square outlines the various processes that disciples and leaders must undergo in their leadership endeavours.

The Four-Stage Process

They think they’ve got us beat

In Breen’s model, the first stage presents the disciple as incompetent but enthusiastic. According to his framework, they’re eager to get going but aren’t aware of their limitations or the challenges ahead. Breen claims the leader should detail the plan but be essentially authoritative while remaining light on the details. In his description, the disciple’s “enthusiasm fuels their confidence, and immediately they step out, put down their nets, and follow” the leader. Breen characterises them as “confident but incompetent - they have no experience to base their confidence on”. The leader, he argues, should be “directive and not particularly democratic” and should not begin with “consensus-style leadership”.

Breen describes stage two as when things start to get tough. In his framework, the disciple’s initial confidence wanes as they face reality, while the leader shifts to a coaching and shepherding role. D2 is when, according to Breen, “the disciples become aware that they really have no idea what they are doing”, and their confidence “hits rock bottom”. He claims, “Disciples aren’t having fun anymore! They start questioning and doubting their call and their decision to follow”. Breen then prescribes that the leader adjusts their approach. In his model, the relationship deepens as the leader “becomes their Shepherd, demonstrating the Father’s grace and love” and “looks for ways to spend more time with them”. According to Breen, the leader must “clear his or her schedule and spend time down in the pit with the individual or team going through D2” to “offer God’s grace and encouragement”.

In Breen’s third stage, he claims that the disciple enters a period of confidence and competence, beginning to develop as a disciple. At the same time, the relationship with the leader evolves into one of friendship and shared purpose. According to his framework, the leader’s style shifts to be more collaborative and pastoral. Breen describes how a “renewed confidence based on experience” begins to emerge in the disciples. In his account, the relationship warms significantly: “They have communion together. They laugh more”. He portrays a sense of community and shared purpose, where “they love to hang out together, share the workload, and linger after teaching sessions to discuss what they have heard”. Breen claims the leader’s style changes “dramatically from a directive style to gathering consensus” because the followers now have the “experience and vision to make their opinions worth considering”.

In Breen’s final stage, he presents the disciple as now competent, confident, and empowered. According to his model, the leader’s role shifts to one of delegation, commissioning the disciple to replicate the process with others while the relationship evolves into a partnership. Breen describes disciples as “empowered with confidence and competence as a result of their deeper relationship and ministry experience with Jesus”. In his framework, their enthusiasm “has deep roots in confidence, brought about by a strong feeling of competence”. Crucially, Breen claims their “confidence is in God, not themselves. They no longer rely on themselves; they trust God to complete what he starts”.

Breen’s four-stage framework offers a complete developmental arc. But what is the real-world result of this process? What does it build in a person’s life?

The Architecture of Control

The framework may be sold as a path to spiritual maturity, but its relational dynamics create something else entirely. The model’s natural effect is to foster a deep dependency between a disciple and their leader, established through an engineered cycle of crisis and rescue.

Brute Forced Dependency

We want your homes, we want your lives

We want the things you won’t allow us

The system explicitly filters for compliance, instructing leaders to tell dissenters that “they can get on board somewhere else”. This control over the environment is absolute. Breen states with clarity: “If you lead a Huddle, then it is your Huddle , and you set the terms, including who you have chosen to disciple and invite”. He positions leaders not as neutral “facilitators” but as active “disciplers” and gives them license for unpredictable behaviour, advising that “you will want to shake things up from time to time”. This combination is highly volatile, creating a high-control group where a leader can keep members off-balance and dependent.

This risks a cohort of followers who, according to the system’s description, are “confident but incompetent” - enthusiastic yet disempowered from the critical inquiry necessary to develop actual competence. The designed outcome is a group primed for the crisis that Breen’s model requires.

The model then presents the subsequent crisis stage not as a possibility but as a mandatory and unavoidable step , stating plainly that “D2 is inevitable”. The conditions established in Stage 1 create an environment where this crisis becomes highly likely, if not inevitable. This dependency is then powerfully intensified in Stage 2, which functions as a period of induced crisis. The model requires that the disciple’s confidence “hits rock bottom” and that they descend into a “deep pit of despair”, questioning their very call. The “pit of despair” is not stumbled upon; it is structured into the methodology.

This blueprint of a manufactured crisis has had devastating , real-world consequences. Consider the documented experience of Matt Drapper, who enrolled in a Breen-modelled discipleship year in 2015

After a period of intense initial enthusiasm (D1), Drapper attended a “Prayer Team weekend”, during which he experienced what closely resembles the D2 crisis Breen’s model demands. The church’s teaching pre-emptively framed any resistance to the process - even “wanting privacy” or “questioning” - as evidence of demonic influence. In a one-on-one session, having already “confessed” his vulnerabilities in a detailed form, Drapper was subjected to an exorcism11. Church elders led him in a pre-written prayer to “break the power of homosexuality over me” and renounce the “demons” of “Victim … and Homosexuality”.

Drapper describes a violent internal struggle where he felt a part of himself being forcefully expelled from his own body. At this moment of maximum vulnerability, an elder validated the trauma by claiming, “I can see demons…marching out the window!”. Drapper’s experience is a stage 2 crisis. In the aftermath, feeling like a “skeleton” who had been “scooped out,” Drapper was given the prescribed leader intervention. His Form leader instructed him, “You have to keep living out your healing… And start living as if it is completely true”.

At this point, the system positions the leader as the sole source of comfort and validation. Such intervention forges the intense emotional bond Breen’s model requires - a bond rooted not in mutual strength , but in the disciple’s structured or induced despair and the leader’s timely, system-affirming intervention. Following this, Drapper’s behaviour perfectly illustrates the resulting dependency: he became addicted to the “high on Jesus”, constantly seeking “more and more infilling” from leaders to avoid the reality of his trauma. The system did not heal him; it broke him and then made him dependent on the very ideology and the people that caused the fracture.

Breen himself acknowledges the psychological impact of this cycling dynamic. Writing about what makes his Huddle methodology so effective, he reveals something that should deeply concern any leader considering his approach:

“Huddles work in this way because, once people experience invitation and challenge, it’s addictive . Why would you want to leave that kind of relationship? Someone who cares enough about you to give you all of their life but loves you enough to take you to the place where you live out of your true identity … even when getting you there may be hard sometimes. … Our experience is that many people (though not all) experience more spiritual growth and breakthrough in their first 6-9 months of Huddle than in their previous five years. When people have this kind of growth, they are ruined for life . They can’t go back to a place where they aren’t experiencing both invitation and challenge. They want that kind of discipling environment and relationship.2”

Please, read that again.

Reader, please note - these are not my interpretations of the effects. I haven’t included this section from Building a Discipling Culture out of context. These are Breen’s own words, as found in his foundational manual on discipleship, discussing the ‘balance’ between invitation and challenge.

What’s remarkable is how precisely these “features” align with what the Church of England now recognises as indicators of spiritual abuse. When someone emerges from a spiritual environment unable to function in normal church relationships, when they describe their experience as “addictive”, when they feel they can never return to an ordinary Christian community - are these signs of spiritual maturity? Or red flags ?

The Church of England’s safeguarding guidance specifically identifies isolation from normal relationships, loss of self and identity, and feelings of powerlessness as impacts of spiritual abuse. Yet here’s Breen, documenting these exact outcomes as proof his system works. What trauma specialists call “trauma bonding,” what safeguarding experts recognise as coercive control, Breen packages as discipleship success stories.

We’ll examine these dynamics in detail later: how enforced accountability becomes a weapon, how the threat of spiritual consequences keeps people trapped, and how public shaming masquerades as “challenge”. But for now, sit with this: the man who compared Jesus to a horse trainer proudly documents that his followers become psychologically dependent on the very system that breaks them.

Breen’s own words confirm the outcome, but to prevent this from happening again, we must understand the mechanics. The dependency Drapper experienced was the result of a process designed and scaled with utter carelessness.

Stop for a moment and think about your closest relationships. Chances are, many were forged or deepened during difficult times - when someone showed up at 2 am because you needed them, when they sat with you through loss when you weathered a crisis together. You know that feeling of profound gratitude toward someone who was simply there when everything fell apart. Such a bond stems from introductory human psychology, and there’s absolutely nothing wrong with it. It’s a part of what makes us human. These bonds are precious because they emerge from a genuine need met by an authentic response. Now, here’s what should raise your eyebrows: Breen’s model takes this beautiful, organic process and brute forces it. Instead of being present during natural struggles, leaders systematically create artificial ones. They’re manufacturing the very crisis that makes their intervention seem so gracious. When someone pulls you from a hole that they dug, your gratitude becomes their weapon .

After what is often called the ‘D2 crisis,’ the mood shifts dramatically. In Stage 3, the disciple is brought closer—suddenly trusted, welcomed, and even valued. Their insight now matters, but only because they’ve made it through something hard. That sense of inclusion doesn’t come freely; it’s granted by the same leader who triggered the rupture. The contrast can be disarming. Gratitude flows toward the person who both caused and resolved the pain.

When describing the shift to Stage 3 (D3), Breen claims that the leader can now adopt a consensus style because the followers have the “experience and vision to make their opinions worth considering” 2. This single phrase reveals much. It explicitly states that a disciple’s opinion is only considered “worth considering” after they have been through the engineered crisis (D2) and the subsequent period of leader-centric rescue and bonding. This dynamic effectively invalidates the thoughts and opinions of anyone who has not yet been through the “pit of despair”. Such invalidation indicates a system where only those who have been successfully broken and remade by the process are given a voice. At the same time, the perspectives of emotionally resilient newcomers or discerning critics are dismissed by default as not being “worth considering”.

The process culminates in the fourth stage, where the disciple’s sense of self has undergone a fundamental alteration. While their confidence is described as being “in God, not themselves” - language that echoes healthy biblical dependence - Having been systematically taught to distrust their discernment through engineered crisis, what emerges is conditioned dependency on the very system that broke them down. The empowerment they receive becomes a commission to replicate this same cycle of creating dependency on others, ensuring the perpetuation of the relational dynamic.

Ultimately, the entire four-stage design appears to be a self-validating system , engineered to guide disciples while simultaneously proving the necessity of its methodology. The “pit of despair” in Stage Two serves as the central, indispensable event that forges the specific, intense bond of dependency between the leader and disciple - a bond that may not exist in its absence.

Within this framework, traditional metrics of success are rendered invalid. A perfectly competent leader who starts a group and succeeds from the outset, enriching the lives of those around them through positive growth, is not considered successful by the model’s logic. Their journey risks being seen as illegitimate because it bypasses the prescribed cycle. Success, in this system, is defined by the shared experience of falling into a manufactured crisis, into the arms of a kind, supportive, and gracious leader - being “saved” by them - and having that dependency formally acknowledged as the foundation of the relationship.

This same logic extends to the disciples themselves. A disciple who already acts with humility, accepts and is aware of grace, and possesses the resilience to navigate challenges without a crisis would undermine the designed effectiveness of the process. Their maturity would prevent them from experiencing the necessary “pit of despair,” making the leader-centric rescue impossible and preventing the intense, dependency-forming bond the model requires. The system has no mechanism for disciples who don’t need to be broken and remade according to its specific formula; their pre-existing spiritual and emotional health becomes a fundamental incompatibility.

This might explain why Breen-influenced churches consistently target young adults and students - demographics naturally characterised by identity uncertainty, transitional vulnerability, and limited life experience. The model requires psychological fragility to function, making established adults with mature support networks, financial independence, and developed discernment poor candidates for the prescribed dependency cycle.

Breen’s expectation of psychologically vulnerable disciples reveals something profound about the system’s underlying mechanics. A framework that cannot accommodate emotional resilience, which breaks down when confronted with spiritual maturity, and that depends on creating rather than healing psychological distress is not operating according to healthy developmental principles. Instead, it appears to follow patterns that have been extensively documented in a very different context - one where the systematic creation of dependency through destabilisation has been recognised as fundamentally harmful in abusive relationships.

Drapper’s documented experience reveals the full extent of systematic harm that has been widely misunderstood. Following his formal complaint12 in November 2019, an independent investigation by Barnardo’s upheld all four aspects of his allegations about his treatment at Network Church Sheffield. While the conversion prayer weekend where he was subjected to exorcism was undeniably horrific, focusing solely on that event misses the broader truth: Drapper endured an entire year of systematic psychological conditioning designed to break down his resistance to the church’s position on sexuality.

The prayer weekend was not an isolated incident of conversion ministry - it was the devastating culmination of a sustained campaign of psychological manipulation. The Barnardo’s report confirmed that Drapper was subjected to a church culture with the “firm belief that these individuals, in due course, with prayer and encouragement, will understand the need to be transformed”. What this meant in practice was that every aspect of his discipleship year became a tool for targeting his sexual identity.

Breen’s approach provided the methodology for this extended assault on Drapper’s sense of self. The leaders implementing these techniques had been given what was essentially a ‘conversion ministry hammer’ - a coordinated method for breaking down resistance and creating dependency - and Drapper’s sexuality became the nail to be hammered into submission. The destabilisation, manufactured crisis, rescue, and bonding cycle was weaponised against his core identity with devastating precision.

Some will argue that Drapper’s experience has been “dealt with” through the Barnardo’s investigation. However, Barnardo’s described Network Church Sheffield’s reluctance to engage and their insistence on limiting the terms of reference before the investigation commenced. Even if Barnardo’s had been aware of Breen’s model, they did not have permission to investigate it as a deliberate methodology. To be clear, Breen’s techniques, which Network Church Sheffield enthusiastically endorsed as a discipleship system , were not within the scope of an investigation into spiritual abuse during their discipleship training year .

What makes Breen’s model so dangerous is that it equips leaders with sophisticated tools of psychological manipulation while convincing them they are providing pastoral care. The leaders likely believed they were helping Drapper. Still, the methods they had adopted progressively eroded his autonomy, isolated his resistance, and conditioned him to view his own identity as the problem requiring their solution.

The result was not just a horrific weekend but months of constant psychological calibration designed to reshape fundamental aspects of who Drapper was. His documented experience of becoming “addicted to the high on Jesus” while desperately seeking “more and more infilling” demonstrates how Breen’s system transforms theological disagreements into campaigns of psychological reformation - dismantling a young man’s sense of self to rebuild it according to the leaders’ theological preferences.

Ultimately, this is not an argument about theology but about conduct. No belief can justify the use of psychological coercion. When spiritual authority is weaponised against a person’s identity, it creates a form of captivity that causes profound harm, regardless of the leader’s sincerity.

These manipulative dynamics are not a mystery—they are well-documented, and their outcomes are predictable. We must recognise this pattern for what it is to prevent a methodology that packages psychological coercion as pastoral care from harming anyone else.

Clinical Evidence for Trauma-Bonding

You could end up with a smack in the mouth

Just for standing out, now, really

In 1981, Donald Dutton and Susan Painter13 interviewed women who remained with violent partners even when leaving was possible. They documented a powerful emotional attachment that held fast despite the abuse. They document two consistent conditions. First, there is a significant power imbalance. Second, a cycle that veered between cruelty and sudden affection. This unpredictability affects the brain’s chemistry. Sporadic comfort releases a more substantial dopamine surge than steady kindness, gradually reshaping the brain’s attachment systems in response to that spike. What emerges is a bond built on volatility, not safety. Dutton and Painter showed that such bonds can displace healthy attachments and recast manipulation as love.

How Trauma-Bonding Works

Breen’s invitation-challenge rhythm reproduces the pharmacology of dependence. A leader who controls every variable first withholds approval, then leads the disciple into a “pit of despair,” and finally supplies just enough warmth to make them feel like their leader is rescuing them. Where belonging rests on that oscillation, discipleship gives way to conditioning. Testimonies from Breen-run churches—people defending the very process that unsettled them—confirm the laboratory findings.

Patrick Carnes later traced the same neurochemical storm in what he called betrayal bonds . Carnes’s clinical files14 show an initial period of “ love-bombing ” (an initial flood of affirmation), a plunge into devaluation (criticism, public shaming, silent treatment), and at last a selective rescue that the survivor experiences as grace. Brain-scan studies Carnes cites register cortisol and amygdala spikes during devaluation, followed by a dopamine rush when rescue arrives—an emotional whiplash that welds memory to emotions. In Breen’s vocabulary, the first phase is “invitation”, the second hides inside the elastic term “challenge”, and the third arrives as a breakthrough. Rehearsed often enough, the cycle trains followers to crave the very hand that controls them.

Lenore Walker’s Cycle of Abuse 15, distilled from hundreds of domestic violence cases, describes tension building, an acute incident, and reconciliation so powerful she likened it to “miracle glue”. Breen declares the acute incident inevitable - Stage 2 of his four-stage square - then prescribes Stage 3 communion and laughter as proof of God’s favour. By insisting this rhythm is “the Jesus model,” the framework baptises an abuse cycle as orthodox discipleship.

Objections typically insist that domestic violence research is too stark a lens for church life. Yet Dutton and Painter themselves tested their theory on cult members, hostages and abused children: wherever one authority dispenses both threat and comfort, the same neuro-chemical trap appears. The theological overlay intensifies it; when the intermittent reward is framed as divine approval, resistance feels like insubordination to God , amplifying self-blame and cognitive dissonance - precisely the profile described in clinical studies of religious abuse.

The BITE Model: Four Lanes of Control

For an analysis tailored explicitly to faith settings, we turn to Steven Hassan’s BITE model, the culmination of decades spent guiding individuals out of high-control groups. Hassan describes four concentric arenas of manipulation: behaviour, information, thought and emotion. Breen’s system engages every arena. Invitation-only Huddles dictate diaries, jargon and social networks, locking down behaviour. Leaders teach LifeShapes behind closed doors and warn that public explanation “doesn’t work”, thereby controlling information. Dissent is re-labelled pride or “lack of kingdom vision”, narrowing thought. Emotional life is steered by the invitation-challenge seesaw that Breen openly calls “addictive”. Hassan’s warning is blunt: when all four levers move at once, “ the authentic self is eclipsed by a cult-self that reflexively protects the group ”. Breen’s marketing line - “Why would you ever leave a Huddle?” - could have been lifted from Hassan’s case notes.

Outcomes on the ground match the science. Breen celebrates disciples who find ordinary congregations unlivable; trauma specialists classify the same symptoms as post-cult adjustment disorder. Matt Drapper’s journal charts the classic betrayal-bond curve: resistance, leader comfort, exhaustion, and renewed submission.

When a discipleship scheme produces addiction instead of freedom and dependency instead of maturity, the clinical parallels become undeniable: coercive control is in play. Pious vocabulary cannot transmute that outcome into health. From neuro-chemistry to survivor narrative, the evidence converges on a single conclusion: Breenism hijacks the attachment circuits God designed for genuine community and re-routes them toward the retention of authority. Both the science and the gospel insist we name it for what it is.

Documented Church Devastation

We’re making a move, we’re making it now

We’re coming out of the sidelines

I’ve come to see that access and exclusivity aren’t just features of Breen’s methodology — they’re central to how it holds power. But you only start to grasp the full weight of that once you look at what’s happened in real churches. Reports tell a familiar story from different denominations from different cultures. The pattern is one of deep division. Congregations torn apart by systems that decide who’s in and who’s out — and make belonging feel like something you have to earn.

Scale of Opposition

The breadth of opposition is striking. One of the few places where affected church members could find information about their experiences was a 2013 blog post by Keith Schooley. By 2014, that single post had generated over 460 comments from people across the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia, all reporting remarkably similar experiences of church division, declining attendance, and systematic exclusion.

The pattern of church decline is consistent and severe. North Heights Lutheran Church in Minnesota reported a nearly 40% drop in attendance during their involvement with 3DM, which ultimately led their council to vote unanimously to remove the program, resulting in the voluntary departure of their senior pastor and two associate pastors. Ebenezer Lutheran Brethren experienced similar devastation, with their pastor eventually resigning amid the turmoil. One commenter reported that their church had declined from 150 regular attendees to approximately 50. Another described their congregation as “ decimated ,” while multiple testimonials reference churches losing half their membership.

The financial burden compounds the human cost. Churches report paying over $ 16,000 for two years of ‘coaching’, while individual participants face monthly fees of $100 for huddle participation. One commenter noted the cruel irony: “Churches don’t have that sort of money without cutting elsewhere, i.e. staff - vital youth workers, talented … ministry workers”.

Systematic Exclusion

‘Cause they just wanna keep us out

The testimonials reveal a consistent pattern of exclusion across multiple churches. Church members report being labelled as “not a person of peace ” for declining huddle participation or as “ resisters ” for questioning the methodology. Multiple accounts describe ministry terminations for those “not part of the discipleship huddle,” leadership positions restricted to those who “adhere totally to the 3DM methodology,” and programs introduced “under the radar ” or “quietly and without the congregation knowing.” The geographic spread, from Minnesota to Sheffield, UK, across Lutheran, Anglican, and evangelical churches, and the similarity of language in independent testimonials suggest that these experiences reflect more than isolated incidents.

The human cost is documented extensively: churches report attendance drops of nearly 40%, congregations are “decimated” and “dwindled,” and lasting “tension and disunity” persist years after implementation. Hundreds of detailed testimonials from multiple countries describe remarkably similar patterns of division and decline. When a discipleship system consistently correlates with church splits, pastoral resignations, and mass exodus of long-term members across diverse contexts, questions arise about whether exclusivity represents an unfortunate side effect or an inherent risk within the methodology. The answer to that question becomes clearer when examining how Breen himself addresses the inevitable feelings of exclusion his system creates.

The Theological Justification

We don’t look the same as you

And we don’t do the things you do

But we live around here too

When teaching on this subject, Breen directly addresses the feelings of jealousy and exclusion that an insider/outsider model might create. To justify this, he instructs leaders to model themselves on Jesus, writing:

Look once again at Jesus and his relationships. He had three very close friends - Peter, James, and John. What did the other nine think of this? Apparently, Jesus didn’t care what they thought . And what did the seventy-two think of the twelve? Jesus had a closer relationship with the twelve than the seventy-two, but again, he doesn’t try to be fair . He needed close friends in his life and did not shy away from inviting the three, then the twelve, into a tighter circle than others.2

This passage offers a clear window into a core theological assumption of the model. Its implications can be understood in three parts.

First, it presents a contentious reading of the Gospels. It takes the descriptive fact of Jesus’ inner circle—a unique group of eyewitnesses—and turns it into a prescriptive model for creating permanent tiers of access within a church. Breen uses this to counter what he calls the “false idea that we must maintain a professional distance” from congregants.

Second, it provides a permission slip for pastoral malpractice . It gives leaders a spiritual justification to dismiss the pain and legitimate grievances of those who feel excluded. Breen advises that leaders cannot “escape the human need for close relationships just because others might be jealous”. Breen thus reframes the natural human cost of creating in-groups as an acceptable consequence of emulating Christ.

Finally, the argument rests on a problematic portrayal of Jesus’s approach to relational care. The word “apparently” implies a lack of care towards Christ, while the assertion that Jesus “doesn’t try to be fair” sets a precedent for a leader’s preferential relationships.

But you’re still not convinced, are you? Despite the theological distortion, despite the clinical evidence, despite the documented devastation across multiple churches - somewhere in the back of your mind, you’re thinking: “Surely the tools can be separated from the man. Surely his restoration process means something. Surely all those leaders can’t all be wrong.” If that’s you, then this section is specifically for you. Because I suspect those very doubts you’re feeling right now were carefully engineered.

Engineered Restoration

The first part of this investigation focused on the letters - the ones Breen released after his resignation. It examined how closely they followed his own published playbook on Christian communication strategy. That article only becomes essential if this one leaves you conflicted. You might wonder: Is it fair to critique a man who has publicly shared a journey of confession and restoration? The issue here isn’t Breen’s path to restoration - anyone seeking improvement deserves support, and the grace of God is freely available. The concern lies with how that personal restoration has been publicly framed and promoted in ways indistinguishable from a marketing push, seemingly engineered to reassert readiness for ministry. Breen’s letters appear carefully crafted to provoke hesitation in critics, leveraging emotional responses structured by his communication strategy - connect your message to the gospel, structure it as a hero’s journey, and guide your audience toward acceptance. His letters follow his teachings closely. They are textbook. His textbook, Speak Out 1. But the letters themselves are only half the story.

Most troubling of all, Breen’s public restoration process reveals how deeply these control patterns are embedded in his approach to relationships. Even when supposedly submitting to accountability, he replicated his methodology exactly: invitation-only participation, leader-selected team members, exclusion of critical voices, and careful narrative control. This isn’t merely a biographical detail - it’s evidence that the controlling dynamics aren’t just taught techniques but fundamental to how Breen operates in all contexts , including those specifically designed to provide oversight and accountability. When contacted for this article at Breen’s suggestion, the chair of the restoration team did not respond.

The mechanics reveal the deeper pattern. Breen personally selected his accountability partners, replicating his invitation-only Huddle methodology. Most remarkably, he included someone he described as his ‘ spiritual mentee ’ - a curious word choice for an author who has recently published a fourth edition of his book on ‘discipleship’ - to validate his restoration. Even his public narrative followed the prescribed four-stage arc he teaches others: crisis, the pit of despair, leader intervention, and empowerment. A restoration process designed according to Breen’s methodology, led by individuals formed within it, could only produce what that methodology always produces: submission disguised as accountability.

The predictable result: a process designed not for genuine accountability or renewal but for the continued influence of Mike Breen’s ministry.

Conclusion

We won’t use guns, we won’t use bombs

We’ll use the one thing we’ve got more of

That’s our minds

And brothers, sisters, can’t you see?

The future’s owned by you and me

Breenism risks appearing to conjure a counterfeit Christ - part strategist, part animal trainer - who sizes up every heart as though it were a dial to be turned, tightening invitation here, ratcheting challenge there until the wall cracks and compliance feels like devotion. In this telling, power is the sacrament : the more finely a leader modulates the room’s emotions, the more “Christ-like” he appears. The bruises such mastery leaves behind are re-named “breakthrough”, and the gasp of relief that follows manufactured distress is praised as “spiritual hunger”.

The Jesus who walks out of the Gospels moves in the opposite direction. He kneels to wash feet that will soon flee, feeds bodies that will still doubt, and calls his follower’s friends when they have offered him nothing but misunderstanding. He gathers the unteachable, the overconfident, and the chronically wounded and bears their chaos without ever exploiting it. Where the counterfeit wields uncertainty to claim allegiance, the true Shepherd absorbs uncertainty to give rest. One Christ liberates; the other manipulates. They inhabit different kingdoms, and congregations should be wary of trying to serve both.

May the communities reading these words find courage to refuse easy fixes, humility to listen long, and steady hope in the Good Shepherd. It demands we ask which gospel we are advancing - the one found in scripture or a different gospel, which, as the Apostle Paul warns, is “ really no gospel at all ” (Galatians 1:7).

Given the documented risks, these methods demand critical re-evaluation and must be discontinued. Once the coercive architecture is dismantled, what remains is arguably the system’s least controversial element: a simple triangle, used as a visual aid for the long-standing theological principle that a healthy Christian life integrates the Great Commandment and the Great Commission.

Follow This Investigation

Receive new long-form investigations and essential updates. No spam or noise, just rigorous work

Your email address will be stored securely and never shared with third parties. We respect your privacy and only send occasional updates.

References

Footnotes

-

Julie Royes, ‘Pastor Mike Breen Resigns from Ohio Church Over Alleged Clergy Sex Abuse’ ↩

-

Church Times. Resources churches: the Marmite effect. 9 August 2024. Available at: https://www.churchtimes.co.uk/articles/2024/9-august/features/features/resources-churches-the-marmite-effect. ↩

-

Building a Discipleship Culture with Mike Breen YouTube, uploaded by Ordinary Movement, 23 Jul. 2023 ↩

-

Drapper, Matt. Bringing Me Back to Me (2020). ↩

-

The senior leader implementing these techniques was Nick Allan, both a documented advocate of Breen’s methods (having published a 2012 dissertation supporting Breen’s approach) and operating under Breen’s direct spiritual authority. In 2014, the church had formally recognised Breen as “the leader of the movement that this church is a part of” placing him in a position equivalent to a bishop to “speak into its spiritual life.” ↩

-

Technically, the Church of England distinguishes between “exorcism” (which requires episcopal permission) and “deliverance ministry”. However, this distinction is largely procedural rather than experiential. From the perspective of someone undergoing a ritual designed to cast demons from their body, the denominational terminology is irrelevant to the psychological impact. In common cultural understanding, both practices constitute exorcism, and prioritizing technical ecclesiastical distinctions over accurately representing a victim’s lived experience would be inappropriate in this analytical context. ↩

-

A formal complaint by Matt Drapper led to an independent investigation by Barnardo’s, commissioned by a Core Group led by the Diocese of Sheffield. The investigation upheld all four of his complaints regarding his treatment at Network Church Sheffield. ↩

-

Dutton, Donald; Painter, Susan. Traumatic Bonding, 1981 & 1983 ↩

-

Carnes, Patrick. The Betrayal Bond, 2019 ↩

-

Fisher, Bonnie. Encyclopedia of Victimology and Crime Prevention, 2010 ↩

Comments

A Note on Commenting

Thank you for joining the conversation. This space is intended to be a place for support, clarification, and shared understanding for those who have been impacted by high-control spiritual environments. To help create a safe and constructive dialogue, please consider the following guidelines:

- Pseudonym Friendly. You are encouraged to use a pseudonym to protect your identity. If you do, please try to use it consistently across your comments to help with conversational flow. Avoid sharing personally identifying details like specific locations, workplaces, or the full names of non-public figures. Your safety is the priority.

- Offer Support, Not Unsolicited Advice. Simple words of validation like, "Thank you for sharing," or "That sounds very familiar," can be powerful. Please respect that everyone's journey is unique. Refrain from telling others what they should do or should have done.

- Prioritise Your Well-being. Engaging with this topic can be emotionally demanding. It is okay to step away from the conversation if you feel overwhelmed. You are not obligated to answer questions or respond to every comment. Please pace yourself and prioritise your own mental and emotional health. If you're not 100% comfortable with the topic, please don't feel obligated to comment. This post will still be here tomorrow.

- Engage with Grace. Everyone is at a different stage of healing and understanding. It is possible to disagree with an idea respectfully, but personal attacks, invalidation of others' experiences, or shaming language will not be tolerated. Let's aim to make this a space of mutual respect.

About Daniel Caerwyn

Daniel Caerwyn is a pseudonym – an investigative writer exploring systemic causes of organisational dysfunction. He writes with commitment to the Church and compassion for those within it.

Expertise: